Which at first glance appears like an incredibly daft, click bait question but when government scientists investigated this, they came up with a startling conclusion.

In early 1967, a rumour started circulating that Ian Fleming had not written the Bond books single-handedly. Well at least not all of them. This was not some baseless story put about by the forerunners of QAon but from UK government scientists working at the Atlas Computer Laboratory, in Chilton, Berkshire.

The Lab’s front was that it provided free of charge, high-level computing service to research workers in British universities but it was also involved in developing the UK’s new generation of nuclear weapons technology.

The facilities in the photograph above were home to the biggest computer in the country: a Ferranti Atlas 1 (called the UK’s first super computer) but the rather anonymous-looking laboratory was more than a benign home for computer scientists. It was part of the UK government’s Atomic Energy Research Establishment involved in the development of nuclear-based reactors, and new weapon technology (though this was never admitted). In fact their operations were so secret that the files about their work have still not been placed by the government into the public domain.

At the time, Atlas 1 could calculate π to 5,000 decimal places in 20 minutes; square root of 2 to 10,000 decimal places in 14 minutes. It was the most powerful general- purpose super-computer in the world, having 48K words of main memory, 48-bit words, one million words of storage in the main memory or on drums, 16 magnetic tape decks, and a processing speed of about one million instructions per second. Far from impressive today but then at the cutting edge of computing capacity.

In the mid-1960s, the Atlas scientists developed a programme that could analyse and categorise the writing style used by an author, and then identify whether there was any deviation from the norm. This was another front. The underlying programme was developed as a code breaker, one that could take thousands of encrypted communications and uncover their secrets in an up-until-then unimaginable short space of time. Not that there was anything new in terms of the principles. After all, a computer named Colossus had been used in Bletchley Park to break the Nazi’s code in the 2nd World War but this was all together on a different scale and critically was able to identify writing styles; an important part of spying as it could identify messages coming from a single individual even in their encrypted form.

When the programme was pointed towards books, the methodology used was straightforward (and would seem primitive today as it only took samples from a book and not the whole text.) The programme would study these samples and come up with an analysis of the style used including the use of key words such as ‘and’ and ‘that’, and sentence length. This might seem simplistic but the scientists knew these were characteristics that could accurately fingerprint the way an author wrote. Naturally they turned to spy fiction to test their hypothesis, with Ian Fleming positioned centrally in their gunsights.

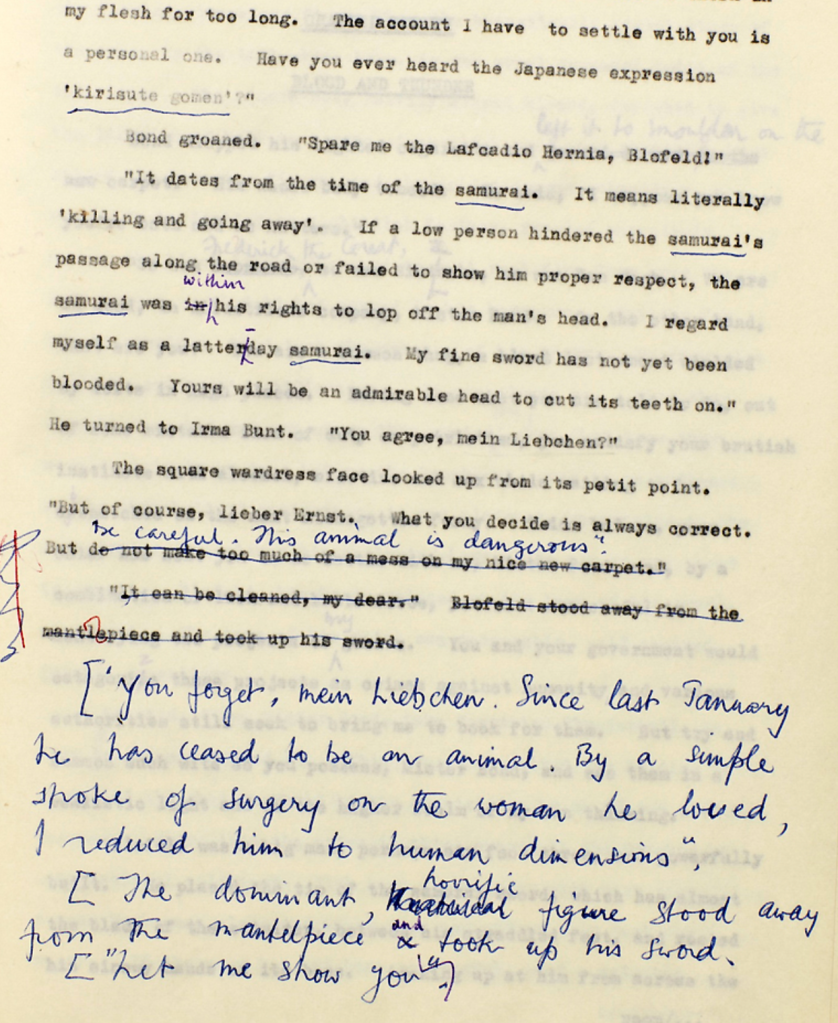

They started by comparing Fleming’s recent work You Only Live Twice and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service to the earlier novels. The analysis showed differences that pointed to the hand of more than one author as Fleming’s writing style had moved away from the style used in his earlier books. On top of that the programme pinpointed an inconsistency of style within the books themselves, and the frequent use of words like ‘hiss’ and ‘sigh’.

Let’s use an example from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. On the first page of the first chapter, the opening sentence is perfect Fleming at only 14 words. But the next two are a mind-boggling 54 and 68 words respectively. Well written? Yes. And too well written for Fleming. In his earlier work he would have never used such long and intricately constructed sentences.

Fleming’s books had always gone through a number of revisions and while these were often minor, William Plomer, his reader at Cape, would sometimes suggest areas where rewrites were needed and he would provide the material. Ergo, some outside influence was always present but not to the scale as found with these later two novels.

Is this completely outlandish? Were there secret forces at play here?

Fleming came to writing from a journalist’s background. His style was to use short sentences, and to be sparse with no lengthy descriptive passages. ‘You damned well had to be neat and correct and concise and vivid,’ he once said. ‘I’m afraid I think Reuter’s training was much more valuable to me than all the reading in English literature I did at Eton or in Geneva.’

‘Bond had had a feeling that this might be the CIA man. He knew he was right as they strolled off together toward the bar.’ Casino Royale

His action moved forward. It was not reflective. He eschewed recaps. He cut anything that might distract or confuse the reader or that did not serve the purpose of driving the plot forward. One example: Bond always used his own name rather than an assumed one or alias when on a mission. The simple reason is that Fleming thought an assumed name would be confusing for the reader and become a distraction.

He had a strict writing routine and would finish a first draft in six weeks having written around two thousand words every morning. That’s a fast pace.

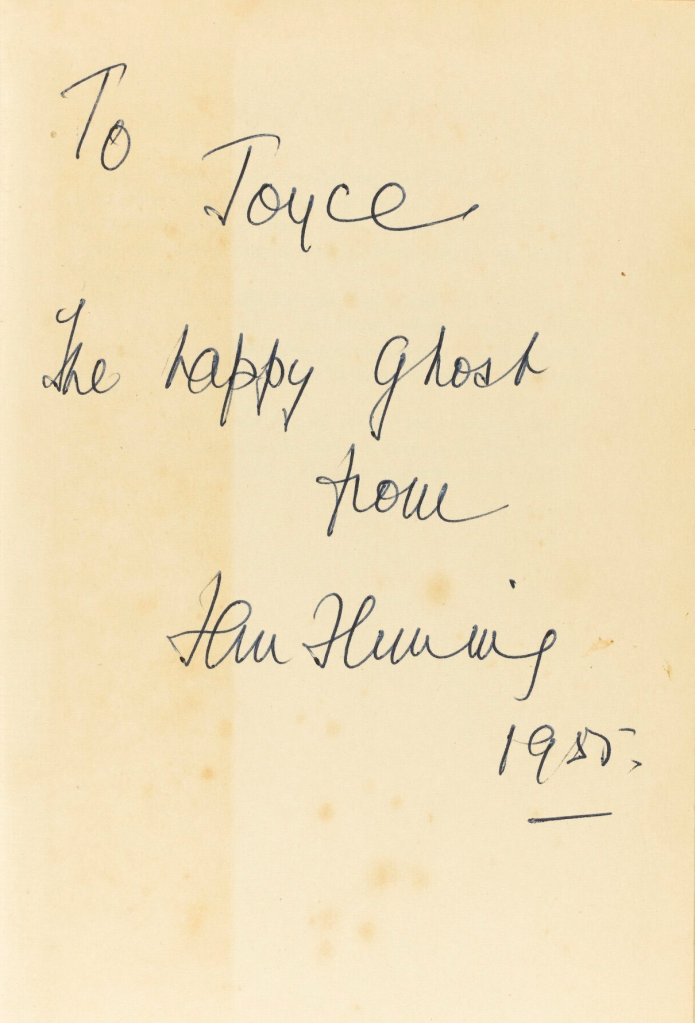

In the 1950s Fleming was writing the Atticus column for The Sunday Times. However it is known that a number of people ghostwrote the column for Fleming including John Pearson (who would later write his biography) but also the less well-known Joyce Emerson. Not that there was anything unusual about this arrangement and it was something employed by most newspapers for these types of columns; nor that the ghost-writer earned, of course, a byline or even the hint of a credit.

Joyce Emerson worked with Fleming on Atticus in the early 50s to the early 1960s. He presented her with a first edition of Moonraker with a cryptic message calling her the ‘happy ghost’ – perhaps she was the real author! No that is too much but she certainly ghost wrote a number of articles in the Sunday Times to help him out when he was distracted by other activities. She was in fact a key journalist on the paper and then the Sunday Times Magazine. One of the stories she worked on was recounting how Piltdown Man was exposed as a hoax, she had a scholarly interest in the modern novel, and she was a broadcaster on the BBC. The cryptic message might mean that she was happy to do ghostwriting without taking any credit whereas perhaps there were others who didn’t.

In short we know that Fleming used ghost writers for his newspaper writing. We also know from his friend Robert Harling that he was idle by nature and could quickly bore.

As he wrote more novels, his style gradually became bloated and grandiose. A number of reasons lay behind this. The first is that he wanted to write the definitive spy novel with more literary pretensions a la Graham Greene rather than some hack pot-boiler. Second, inevitably a writing style may change over time as the writer becomes more confident with their work – and Fleming of course started out seriously doubting his abilities. Third, and specific with Fleming, he started writing late in life, and for his last few years he was an alcoholic and increasingly seriously ill. Understandably, his writing suffered.

That was until his final novel The Man With the Golden Gun, when suddenly it becomes taunt and there are pages when he returns to his old way of writing. Atlas picked this up when comparing it to the previous You Only Live Twice. It found that twice the number of key words were used in You Only Live Twice, and that the average sentence length was also 19 words compared to 11 words in The Man With The Golden Gun (which is what would be expected if more ‘and’ and ‘that’ were being used.).

It is well-known that Kingsley Amis was asked to look at the draft and made a number of both suggestions to the plot and structure as well as specific corrections. Fleming’s Goldeneye maid Violet claimed that his Jamaican friend, Morris Cargill wrote much of it.

Perhaps more telling is Ann Fleming’s observation that in the five months up until his death Fleming was so ill that he was bed bound. And at the start of the year, the broadcaster Alan Whicker who was filming in Jamaica wrote that ‘Fleming was drinking heavily and usually legless by lunchtime. His writing was not going well, if at all.’

It would seem more than plausible to suggest that little of what appeared on the page was original Fleming. The plot and structure yes but the words?

Of course when it comes to the plot, Fleming was the first to admit that he followed a template. So a ghost writer only need fill in the gaps not to devise a new structure. Essentially each book starts with Bond receiving his orders; he makes contact with the villain or vice versa, the woman in introduced, Bond is captured by the villain, tortured, escapes, kills the villain and seduces the girl, who he then loses. As the adventure unfolds there is no introspection, no red herrings, and no twinges of guilt. Bond only takes time out to enjoy food, drink and some sex.

Iniitaly Robert Churchhouse, the senior scientist in charge of the experiment, was enthusiastic about the result and claimed that his computer was both valuable and accurate when it came to analysing text. They had found the initial results fascinating and planned to carry on with their work, in the downtime when they weren’t computing for the secret services.

But Churchhouse mysteriously later refuted his own results and felt they were ‘highly unlikely’ and that the computer’s analysis was unable to accurately determine authorship.

The hypothesis goes as follows. When Fleming started out the books were wholly his writing other than minor corrections suggested by Plomer. As his work became more popular, and he wanted to be seen as more literary, he sought the help of people like Joyce Emerson, as well as being more heavily influenced by the authors he admired. Towards the end of his life, there was greater input from people like Plomer because Fleming’s writing deteriorated. Finally with The Man With The Golden Gun a considerable amount was written by third parties as Fleming was not in a fit state to write.

You must be logged in to post a comment.